Last

summer, two young staff members of the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives

were tasked with organizing the institution’s attic, but their work led to an incredible

discovery. They found fragments of an 18th-century wooden synagogue, which had

been identified in 1911 by Rabbi Ferenc Löwy as "the oldest Jewish temple

in Transylvania". An exhibition showcasing these remains opened yesterday

at the museum.

Nearly

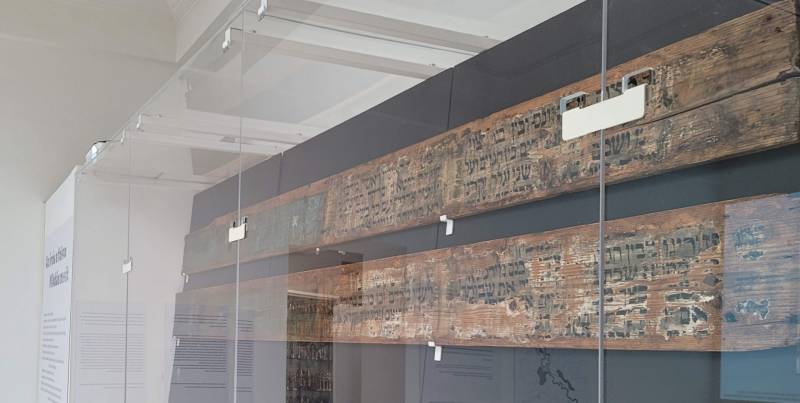

three centuries-old, fading wooden planks are now on display at the Hungarian

Jewish Museum and Archives' new exhibition, titled Writing on the Wall, which

opened on Sunday, February 2.

While these

planks might not seem significant to an untrained eye, museum staff members

Mátyás Király and Balázs Som immediately recognized last summer that they had

stumbled upon an extraordinary find in the attic.

As mentioned at the exhibition’s opening event, Zsuzsa Toronyi, director of the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, had initially only asked the two young men to tidy up the attic. However, the researchers returned with remnants of the wooden synagogue of Náznánfalva, which was built in 1747 and destroyed in the first half of the 20th century.

The

approximately 80–90 kilograms of wooden elements were brought to Budapest by

György Balázs, a former museum staff member, by train from Marosvásárhely /

Târgu Mureș in 1941. He knew that if he did not save these Hebrew-inscribed

wooden fragments, nothing would remain of Transylvania’s only wooden synagogue.

Thanks to

his efforts, the remains survived. However, until recently, only two wooden

panels had been known to experts. It was not until last summer, when Mátyás

Király and Balázs Som accidentally discovered the painted planks, that it

became clear that a significant portion of the Náznánfalva synagogue's remains

had been waiting for rediscovery in the attic.

Over the past six months, extensive research has been conducted by Mátyás Király and Tamás Lózsy to properly present this wooden synagogue in the newly opened exhibition.

Rabbi Ferenc Löwy had previously written about it in the 1911

edition of the Hungarian Jewish Almanac, calling it "the oldest Jewish

temple in Transylvania." Löwy remained interested in the subject for

decades, and in 1934, he even took a journalist from Jerusalem to see the

synagogue. However, they were saddened to find that due to the declining Jewish

population in the area, the wooden synagogue had fallen into disrepair—a fate

it ultimately met within a decade.

The wooden

elements displayed in the new exhibition at the Hungarian Jewish Museum and

Archives are invaluable not only because no other wooden synagogue was ever

built in Hungary or Transylvania, apart from the one in Náznánfalva.

But also

because, even though wooden synagogues were widespread in Polish-Lithuanian

territories from the 16th century onwards, the destruction caused by Nazism

nearly erased them from Europe's built heritage. Today, only a handful remain

in those regions.

The

Budapest exhibition also features the two previously known panels, but the true

highlight is the collection of newly discovered, Hebrew-inscribed, painted, and

restored wooden planks found last summer.

Why Was

There "Writing on the Wall", why was Hebrew text on the planks? At

the opening event, historian Viktória Bányai explained that the Hebrew texts on

the planks had both sacred and practical purposes. In these early Jewish

communities, many people could not afford their own prayer books, so they read

biblical verses and prayers directly from the wooden walls.

The choice

of material was also dictated by financial circumstances. Wealthier Jewish

communities could afford to build synagogues from stone, but in Poland,

Lithuania, and Transylvania, the poorer Jewish populations could only afford

wooden synagogues.

02.27. 17:07, kimenete: 02.28. 18:12

02.27. 17:07, kimenete: 02.28. 18:12

2.jpg)